The University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire College of Arts and Sciences recently received a $30,000 gift to create and endow a fund supporting annual international education experiences for a student in the college. The gift comes from 1971 graduate Eugene Jenneman, who has named the scholarship fund the Eugene Jenneman Award in Honor of Robert C. Elliott to acknowledge the impact one of his UW-Eau Claire professors had on his personal and professional life. Making the gift has been on Jenneman's mind for years, but the relationship he had with professor Bob Elliott has lasted decades.

Jenneman grew up on a dairy farm outside of Bloomer, where the whole world was about as far as you could travel on a Sunday afternoon after church and get back to milk the cows again that evening. He had never set foot in a "big city" until his parents dropped him off to start his freshman year at UW-Eau Claire in 1967. He got there by way of two scholarships he received from Bloomer High School which covered tuition, room and board. Jenneman was the second in his family, including all his cousins, to attend a university. His father, having to take over the family farm and never making it to high school, used to read the World Book Encyclopedia at night, saying, "Get your education. It is the only thing that cannot be taken from you."

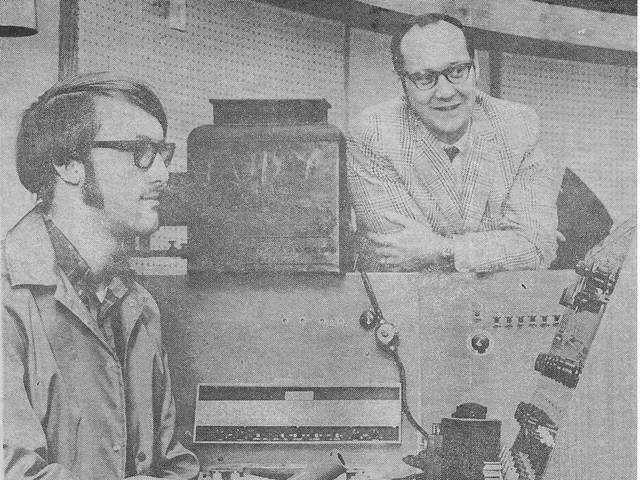

Blugold Eugene Jenneman, left, credits his former professor Robert Elliott for showing him career options that he had never considered. Jenneman has established the Eugene Jenneman Award in Honor of Robert C. Elliott scholarship fund.

He started as a biology major, but quickly changed to physics and chemistry because of a keen interest in astronomy. Jenneman spent many hours in the fascinating planetarium of Phillips Hall, eventually getting a part-time job there as a student working for astronomy professor Bob Elliott. After a semester learning the ropes, Jenneman recalls Elliott coming up to him after class, handing over the keys to the planetarium and saying, "There’s a scout group coming in shortly; go give them a show." With no time to prepare, Jenneman grabbed the keys and gave a captivating lecture on the constellations. He continued to do shows in the planetarium until he graduated in 1971.

What Jenneman didn’t know at the time was that Elliott had the key (literally and figuratively) to what he wanted after graduation: to run a planetarium while teaching high school science. Elliott took Jenneman under his wing as a student operator for UW-Eau Claire's planetarium, but being only 13 years apart, they also became social friends. Elliott would often have Jenneman over to spend time with his wife and family at their Eau Claire home.

Jenneman calls his Blugold experience a "revelation," never missing a single class (even during "anti-war strikes") and becoming involved in draft counseling on campus. Most noteworthy was perhaps the meeting of his wife, Marcia Borell, while working at a coffee house that was in the basement of the campus Newman Center at the time. Marcia, a studio art student, would provide Jenneman a valuable connection to the art department that would prove fundamental in a career transition from planetariums to art museums.

Two weeks before graduation and filled with much of the same apprehension any new college graduate might have, Jenneman walked into Elliott's office to pick up one last round of lecture assignments for planetarium programs. Instead of a stack of papers, Elliott handed Jenneman a plane ticket to Alpena, Michigan, and said, "Here. You’re going to interview to run the planetarium at the Jesse Besser Museum."

Never having been on a plane and never having considered working in a museum, Jenneman trusted Elliott as his mentor and flew to the interview two days after graduating from UW-Eau Claire. He was offered the job and the rest, he says, is history. Through various museum positions in multiple states, Jenneman was recruited in 1988 back to Michigan, to design and build the Dennos Museum Center — about 20 miles from where Elliott spent summer recesses from UW-Eau Claire.

During his career at the Dennos, Jenneman saw Elliott several times. When Jenneman eventually retired from directing the museum in June of 2019, Elliott attended his retirement party. He recalls vividly that he never paid for that initial plane ticket to Alpena — and to this day does not know who did. However, it was Elliott giving him that ticket that would send Jenneman into a world of work he had no expectation of being in.

Elliott was the catalyst for showing Jenneman career options he had never considered. He gave Jenneman the confidence to believe in himself. He gave him a chance when he handed over the keys to the planetarium, sending a message that Jenneman could do this. And he did.

"I knew I wanted to find some way to thank Bob for what he did for me," Jenneman recalls. "When I contacted the UW-Eau Claire Foundation and we talked about giving to UW-Eau Claire, the scholarship became a real option because it was financially feasible for me to do over time, and I could do it in Bob's honor."

The Eugene Jenneman Award in Honor of Robert C. Elliott will provide tuition support for a student pursuing an international educational experience. Over Jenneman's career, international travel has had a profound impact on him and helped him understand the world and its people.

Further, it was Jenneman's college roommate, Dave Van Keuren, who inspired his love for international travel. Van Keuren's mother was a war bride from England, and they promised each other that after graduation, they would backpack through Europe together. Van Keuren was a year behind Jenneman in school, so by the time he graduated, Jenneman was already working at the museum in Alpena. He told the museum he needed the summer off to backpack through Europe with Van Keuren, as he had promised him, and surprisingly they agreed to let him go.

Jenneman recalls seeing major museums for the first time in Europe and came back with many ideas and new ways of thinking that would improve the Besser. From there, Jenneman set down a road of becoming an art museum curator with self-directed tourist travel across the globe. Having been to more than 35 countries with plans to see more, Jenneman believes wholeheartedly in the benefits of international travel.

"Until we see how other cultures, societies and people live, we cannot appreciate our own, what we have, or perhaps question what could be made better in our own lives," he believes.

It is Jenneman's hope that this scholarship will give a student, maybe even someone like a young Gene Jenneman in the 1960s, a chance to travel; perhaps for the first time ever, perhaps overseas, or to somewhere very different than their current culture and experiences.

Jenneman set the scholarship criteria for an international education experience for any major within the college on purpose. Through working in the museum world, travel became the most satisfying part of his career. It also proved that building connections and understanding between cultures is vital for young people, regardless of their degree program.

Being in the museum world, Jenneman is no stranger to fundraising. He understands philanthropy is an essential part of supporting institutions like museums and universities, and has seen firsthand the impact donor dollars had on success.

"We often forget that when we celebrate the achievements of those in the world of arts and sciences, that the building we are routinely successful in has a name on it," Jenneman states. "Were it not for that name, we may not have had the opportunity for our own success and recognition."

Jenneman admits that for most of his professional life he never considered giving in a significant way to UW-Eau Claire. It wasn't until he approached retirement that he realized he would have some resources available; resources that came from his own hard work, of course, but also because he got a start and ample preparation from the university he attended.

"You begin to think differently about life," he reflects. "It is no longer about what can I achieve and earn, but rather what can I do with what I have gained from those years of achievement?"

While Jenneman says he is not wealthy from entrepreneurial efforts like the donors whose names are on many of the buildings we recognize, he credits having a career that allowed him to build a "nest egg" and options to invest in retirement more than he thought he would need.

He made the initial gift to establish this endowment through a required minimum distribution (RMD) from an IRA investment. The gift was sent directly from Jenneman's investments to the UW-Eau Claire Foundation, so he never had to pay taxes on it. The endowment principal is then invested with the UW-Eau Claire Foundation and remains untouched, while the interest it earns each year is paid in the form of a scholarship to a student. He says that what he once saw as his "play money" in retirement is now also his "impact money."

"While not at the level of putting my name on a building, I still have the chance to make a meaningful gift at UW-Eau Claire," Jenneman says. "This enables me to have ongoing impact on at least one student each year well into the future."

The scholarship will be awarded to a student within the College of Arts and Sciences — the home of Jenneman's degrees in physics and chemistry, his wife, Marcia's, degree in art, and Bob Elliott's career as an astronomy professor. The dollars are to support a student participating in an international educational experience in the hopes that they leave that experience more enlightened and well-rounded than when they began.

"When presented with the opportunity from the UW-Eau Claire Foundation to fund a named scholarship, I knew I had to do this to honor Bob and what he did for me — and to finally pay back that plane ticket! I was able to thank Bob in a way that will live forever and impact students where he worked to impact me. It was a no-brainer."

The stars aligned for former astronomy professor Bob Elliott who was able to hear about Jenneman's plan during his lifetime and see the gift be made in his honor on Jan. 25, 2022. Elliott passed away on March 17, 2022.

The gift noted in this piece was received by the UW-Eau Claire Foundation during its Sustaining Human Innovation campaign, which launched in fall 2021. The campaign aims to generate sustainable funding in the form of endowments for student success, faculty investments, programs of distinction and private funding for facilities projects. The goal of the Sustaining Human Innovation campaign is to secure more than $125 million in gifts by June 30, 2026.